- Project

- The Calla Campaign

Empowerment through the integration of innovative new women's health technologies, visual arts, and story-telling.

Learn how a global art and empowerment project grew out of a medical device designed by Duke’s Center for Global Women’s Health Technologies in this behind-the-scenes interview with Libby Dotson (Trinity, '18), exhibition curator.

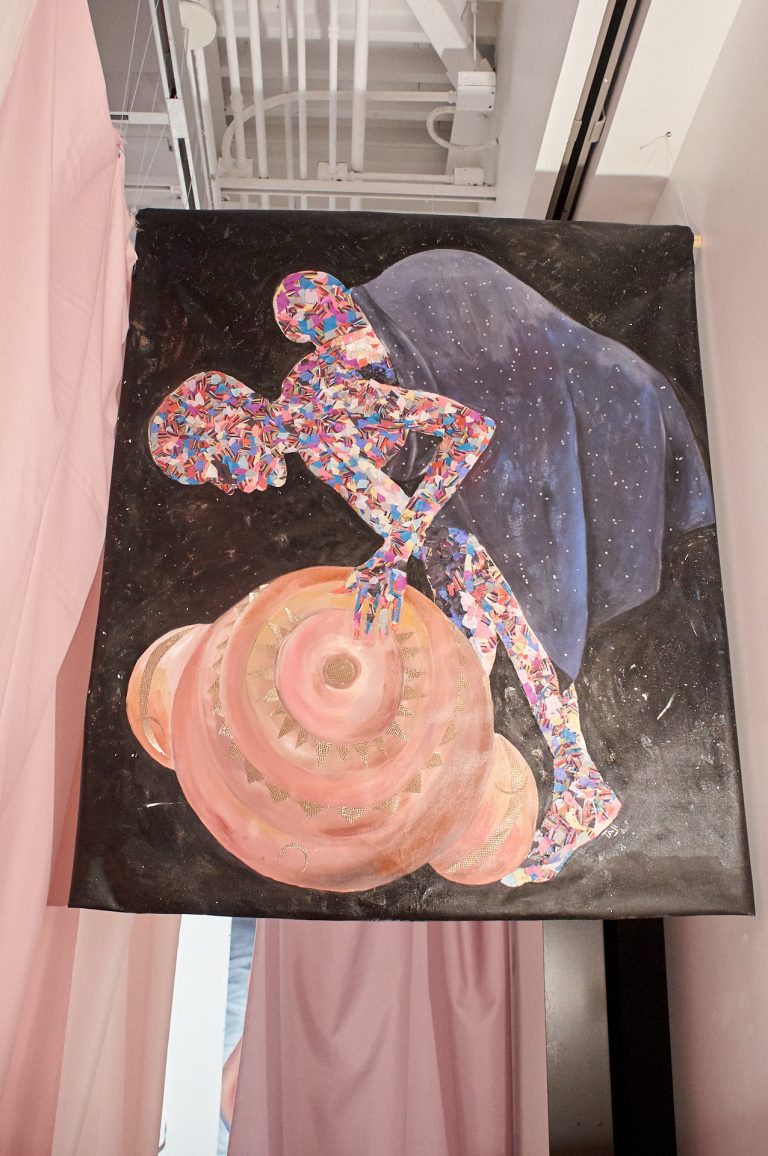

The exhibition (In)visible Organ (on view in the Ruby through March 8) reflects the empowering experiences of women who used the Calla Campaign’s Callascope. The team behind the exhibition aims to increase awareness of cervical cancer globally while combating stigmas around women’s health.

“This art exhibit was an idea that Wesley Hogan, director of the Center for Documentary Studies, and I tossed around over dinner and then subsequently put together in the form of a proposal to the Duke Council for the Arts more than two years ago,” said Nimmi Ramanujam, Robert W. Carr Professor of Biomedical Engineering and director of the Center for Global Women’s Health Technologies.

“While I had an idea what I wanted this art exhibit to speak to, I could have never envisioned what it actually turned out to be—a beautiful collection of women’s voices told in the most authentic and expressive ways about a sacred part of their bodies. Libby and her team achieved a monumental feat and I am so proud of her and grateful to everyone that contributed to this mission. I just hope we can keep the conversation going and not lose the momentum that this exhibit has created,” Ramanujam continued.

In this interview, recent alumna Libby Dotson describes the origins of this innovative art exhibition, her role as lead curator and her hopes of expanding this positive, inclusive conversation on women’s health globally.

Libby Dotson (LD): I grew up in rural North Carolina, where I didn’t have great access to women’s healthcare and my parents were really conservative. I got involved in the Center for Global Women’s Health Technologies (GWHT) and one summer, I went to Guatemala on a GWHT fellowship to focus on STEM empowerment in an all-girls school. After that, I worked in the lab and learned about the global health world. After graduating from Duke, I started working full-time as a post-baccalaureate associate in research. I came on particularly for this project—it was just beginning and needed some extra momentum.

LD: I am the exhibition director and curator. The months leading up to its opening were insane, I was balancing a hundred different things. I had a very good team of people that were working with me—Diane Lee, Andrea Kim and Adair Jones (Duke Arts CAST member). There are a lot of challenges with navigating a large curatorial team because you are balancing different opinions.

LD: Cervical cancer is a very interesting cancer because it is slow-growing, preventable, and treatable. It takes fifteen years to mature to the Stage 2 where it can kill you. And yet, 55% of women who contract it each year die, which is an unprecedented number for a disease with a known virus (HPV). The standard of care for cervical cancer screening in low-resource settings is visualization of the cervix with the naked eye through a speculum. In high-resource settings visualization is achieved with device called a colposcope through a speculum. The colposcope can cost $20,000, which most community healthcare facilities can’t afford. So, the Calla Campaign designed a $500 pocket colposcope, the Callascope. Eventually this device will be able to screen for cervical cancer, but medical device development takes a few years. So right now, it’s an empowerment tool where women can visualize their own cervices.

LD: We did in-depth interviews with women about why they may not enjoy pelvic exams, how they feel about the speculum, and their experiences with their cervices. We sent them home with our device for one week, had them look at their cervices and vaginal canal, and then record an audio reflection. We thought the Callascope was going to just be a cervical cancer screening tool, but we soon realized it led to powerful experiences for women that were almost life changing.

LD: We commissioned artists to create art based on the stories we received, and ultimately opened the platform for artists to create art based on their personal experiences with health and the stigma surrounding what they’ve been through.

The campaign became a bigger idea about exploration. We realized we could do art education workshops. We had two workshops where we had everyone either make the inner reproductive anatomy or sculpt the vulva and then reflect together. This was uncharted territory for everyone. The reflections we got from women were insane. When they came into the vulva sculpture workshop, they were very skeptical. By the end, the reflections we got were so powerful—especially from younger students. They were saying this was empowering, and they felt more comfortable with their body. All of this fed back into the art exhibition.

LD: When I was younger, because of how my parents raised me, I couldn’t talk about sex, I couldn’t talk about my reproductive anatomy, I was taught abstinence in high school, I wasn’t taught about my reproductive anatomy, what’s normal, what’s not, how to take care of it. . . Watching the expression on couples’ faces similar in age to my parents—who you wouldn’t think would be so open—as they entered the space really moved me.

I’m thinking of one couple in particular. Seeing the genuine expression on the husband’s face as he looked at his wife, and then at the speculum, and then the timeline of gynecology. He had more understanding for his wife’s position and the situation that women are in. That made it worth it.

LD: Well, the colposcope is a physical device. Also, you can hand people an infographic and they’ll just throw it away. A lot of people say they don’t care for art or they don’t connect to it, but you’d be surprised how impactful it is when you actually create something physical—it tells a story in a much more compelling way. We wanted this exhibition to be high-impact and shocking.

LD: For our team this is just the beginning. We received Bass Connections funding to do it again next year. We have a graduate student who is going to Ghana where we want to start a campaign around the colposcope. We’re also starting a campaign in Uruguay this summer with mentor fellows. We want this to become global.

LD: Collaborating closely across our disciplines has been one of the biggest challenges for all of us on the team. We relied on candor and honesty, which meant at times we talked across each other at meetings. That is both the most difficult part and the most rewarding part. This is also the way the world is moving. I think the more people learn to interact in a diverse and complicated environment, the better.

“We realized it was bigger than the transcripts from the home studies, bigger than the artists connecting to these transcripts, and bigger than the art education workshops. It was an umbrella of literal and symbolic self-exploration.”

The next phase of the Calla Campaign is to tell the broader story of how new technologies raise historical questions about power dynamics in gender, medicine and global health through a documentary film. Producer Andrea Kim (Trinity, ’18) will interview engineers, artists, and scholars united by a belief in the importance of female reproductive health.

Libby Dotson is a recent Duke graduate (Trinity, ’18) and current associate in research at Duke’s Center for Global Women’s Health Technologies.

Annie Kornack (’20) is originally from Dover, Massachusetts and has loved the arts for as long as she can remember. She is majoring in Psychology with a Markets & Management Certificate, and is also part of FORM Magazine, Arts for Life, Camp Kesem, and the Duke Arts Creative Student Arts Team. Her passion for art and using art to connect with others has led her to call the rich art-loving community of Durham her home away from home.

Empowerment through the integration of innovative new women's health technologies, visual arts, and story-telling.